Welcome to it

Hello friends,

Here we are. Before we dive in, let’s begin with a zen koan (source here), as we have in a few briefs in the past.

Kitano Gempo, abbot of Eihei temple, was ninety-two years old when he passed away in the year 1933. He endeavored his whole life not to be attached to anything. As a wandering mendicant when he was twenty he happened to meet a traveler who smoked tobacco. As they walked together down a mountain road, they stopped under a tree to rest. The traveler offered Kitano a smoke, which he accepted, as he was very hungry at the time.

"How pleasant this smoking is," he commented. The other gave him an extra pipe and tobacco and they parted.

Kitano felt: "Such pleasant things may disturb meditation. Before this goes too far, I will stop now." So he threw the smoking outfit away…

…When he was twenty-eight he studied Chinese calligraphy and poetry. He grew so skillful in these arts that his teacher praised him. Kitano mused: "If I don't stop now, I'll be a poet, not a Zen teacher." So he never wrote another poem.

It’s hard to put pen to paper when financial history - whether measured in Dow points or in the running tally of Federal Reserve stimulus - is being written by the hour. What we write today will indubitably be written over in another week’s time.

It also turns out that even our love of writing about capital markets can lose its luster when you see impassioned plea after plea from main street small businesses in your email inbox. This is all obviously bigger than investing in many ways.

Still, after some silent contemplation, we still think the capital markets remain a valuable lens with which we can approach one part of our world, knowing full well there are countless other such lenses that would be valuable to apply at this point in time. Hopefully we can be of use here.

There are many things rocking financial markets at the moment. Let’s start with one that’s less talked about than the coronavirus.

A precipitous and utter collapse in oil prices

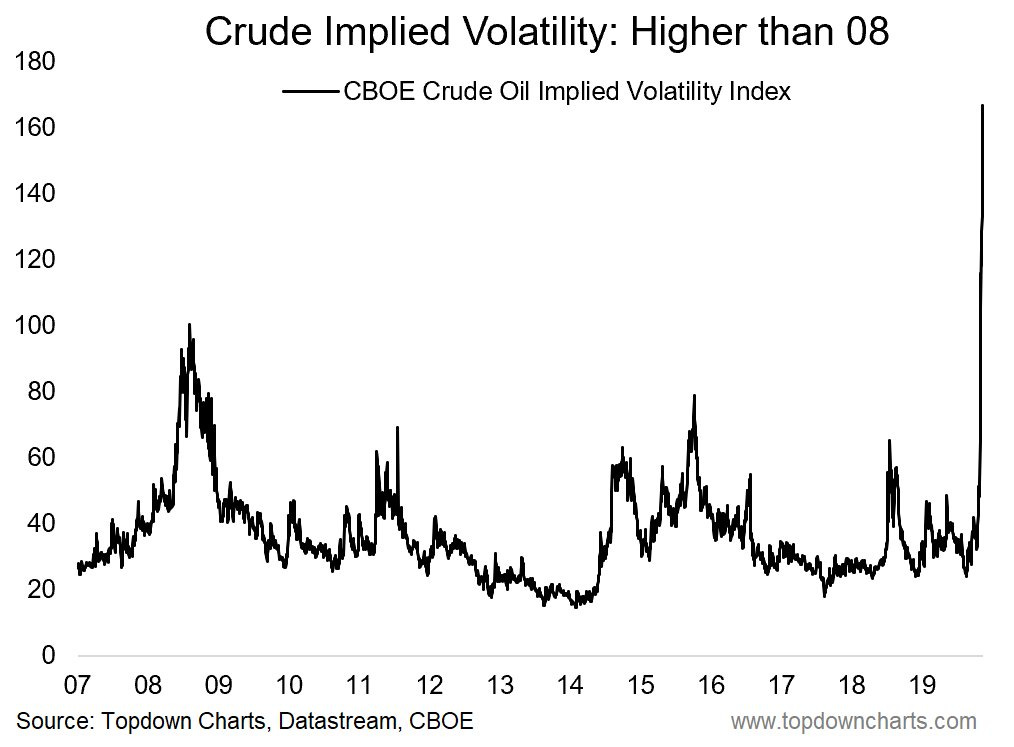

As of this writing, West Texas Intermediate oil is trading around 20 bucks a barrel. That’s down from $60 at the beginning of 2020. Not only is this a sharp collapse in price, but this drop happened as fast or faster than standardized oil markets have seen. For the visually minded, here’s a handy little graph of historical volatility in oil prices.

Make no mistake, the beginning of the end for oil was the slow realization in January and increasingly in February that global economic demand would slow because of coronavirus. This was the first blow.

Putin dumped significant gas on the fire when, at an OPEC meeting where the explicit agenda was to agree to curtail production and prop up prices, Vlad had his lieutenants politely refuse all of Saudi Arabia’s overtures. The outcome? Both countries actually hiked their oil production, igniting an all out price war.

In the immediate aftermath of that meeting, oil prices fell 25%. There’s a larger geopolitical question at play here that we can’t dwell on for more than the following: there’s a significantly non-0 chance that Russia has been expressly biding its time, waiting for a chance to apply max pain to US shale producers.

If so, it chose an opportune moment to strike. Numerous heavily indebted US energy producers are in peril. Chesapeake Energy is likely finished in it’s current form. Others will follow suit.

More importantly, entire countries that rely heavily on oil exports in their budget will be hit even harder. Nigeria, a major producer, is approaching a tipping point. It may need to devalue its currency to pay its debt. These are the types of downstream effects from the financial shocks we’re seeing that no one even has time to talk about.

The biggest economic event of our young lives

It probably is. For one, because it has proven surprisingly easy to shutter entire swaths of the global economy. China and Italy led the way, but now multiple G7 countries have ordered some or all of their citizens to effectively shelter in place. Which is an unprecedented demand shock. Here’s how it’s playing out in big ways:

Marriott’s global hotel business is down 75% from its normal levels.

Delta is reducing its capacity more now than it did in the wake of 9/11

We will see a record uptick in unemployment numbers and new jobless claims. The all time jobless claims high was 695,000 in Oct 82. This will likely get obliterated next week.

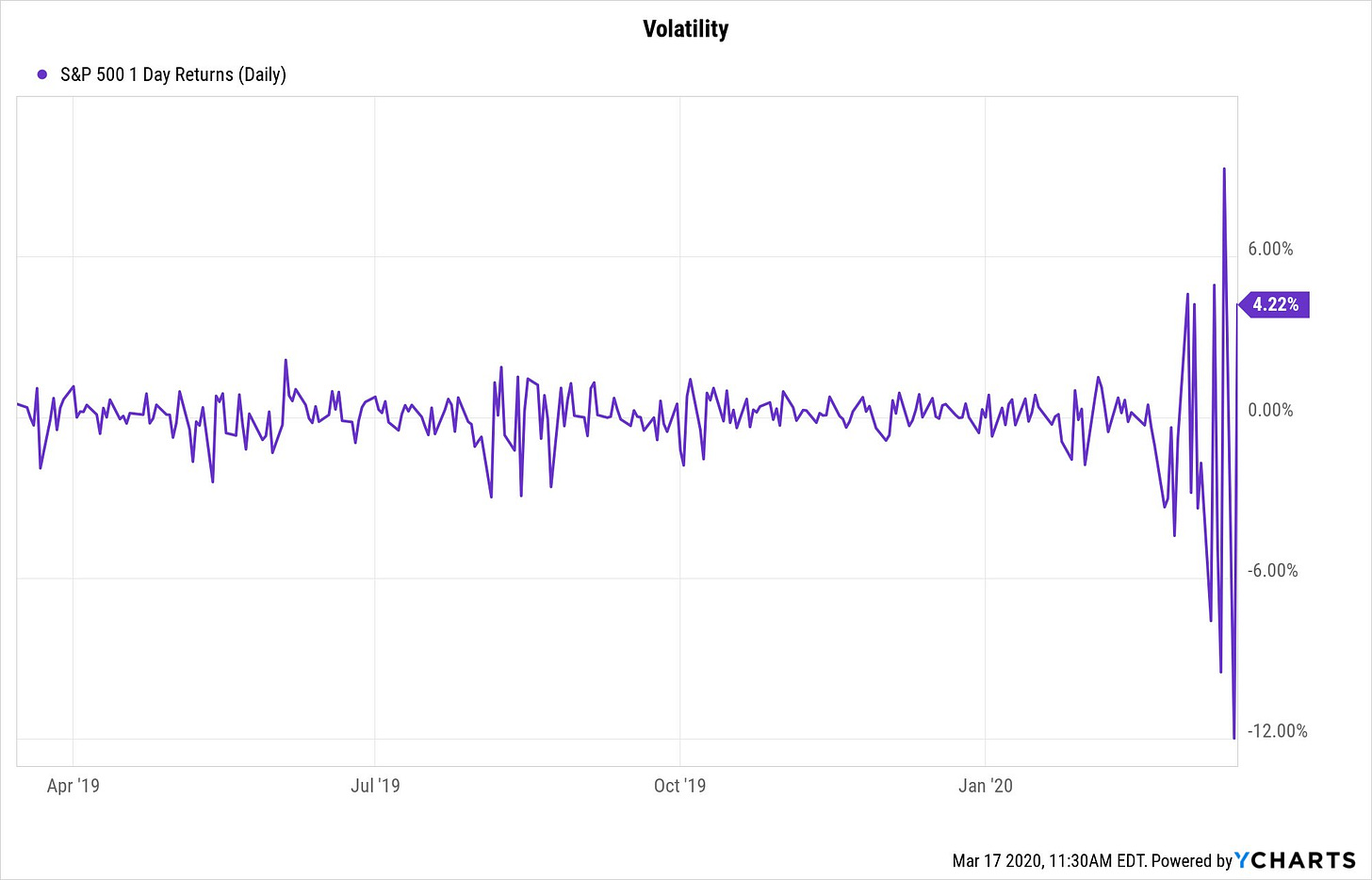

All these stories have played out perhaps most visibly in what was the most volatile week of trading in US equity market’s history. Again, for the visually minded:

It’s five days we’ll never forget, starting at the end of last week:

Thursday -9.51%, Friday +9.29%, Monday -11.98%, Tuesday +6%, Wednesday -5.17%

That includes two of the worst drawdowns ever (on a % basis dating back to 1928).

The market, which is normally a very efficient discounter of probabilities and information, is incapable of reaching any consensus on what the economic fallout of this crisis will be. The problem is that there’s no probabilistic way to estimate:

When businesses will come back online

When consumers will be back out in market

What the effect of fiscal or monetary stimulus (both proposed and already implemented) will be

A few things are for certain. Many American companies have now been caught swimming naked. To explore this further, we borrow from our January newsletter:

Perhaps even more concerning, not even the bastions of American capitalism seem able to resist the call of debt issuance at low rates. McDonald’s ($MCD) is a perfect example; it has issued so much debt in the past years that it has a negative book value (more liabilities than assets).

Will McDonald’s eventually get buried in this debt? Probably not.

Did they make life easier on their future selves, e.g. if rates are higher when they need to raise more cash? Probably not.

That was two months ago. Now, the amount of distressed debt in the US has doubled in two weeks.

While McDonalds will stay open and will probably be just fine, other companies that gorged at the trough of cheap debt and stock buybacks may not fare as well.

Boeing (“$BA”) is a good example.

$BA spent north of $52 billion on stock buybacks from 2008 to 2020.

The entire company now enjoys a market capitalization of only $65 billion

In retrospect, that is is a criminally poor use of cash.

Airlines are a similar case. Is it their fault their business has evaporated? No. Is it their fault that they have no cash on hand to navigate this environment? Yes.

As writes Ben Hunt:

…together with increased debt (+78%), were the engine of an intentional strategy of heightened financial risk taking, such that buybacks were greater than free cash-flow for the group ($37.1 billion)… At every turn over the past six years, management teams at the Big 4 airlines have increased debt and directed their free cash-flow towards anything they thought would prop up their stock price, at the expense of using this money to grow their core business OR protect their core business against a global recession.

Effectively, since 2012, airlines returned more cash to management and shareholders than the they actually generated over that time span.

Here’s what their CEOs enjoyed over the same timespan:

Now, because airlines are in many ways a utility, they’ll get bailed out.

Is this necessary? Yeah.

Is there moral hazard in backstopping companies in bad times with no expectation that they build a fortress balance sheet during good times? Also yeah.

The Policy Response

Part of why we can confidently say that this is the biggest economic event of our lives is because of the ungodly amount of policy action that has already been taken in response to it.

It began on March 3rd with a 50 basis point rate cut by the Federal Reserve outside of it’s normally scheduled meetings. This was already drastic, as actions outside of scheduled meetings signals to investors that there is cause for significant concern.

Since then:

The Fed reduced rates another full 1% to a band of 0-0.25%. They normally move in 0.25% increments — we’ve now reduced rates a full 1.5% in a matter of weeks

Offered $1.5 Trillion in repurchase agreements to ease funding stress for banks (this is the equivalent of overnight lending)

$600B in quantitative easing (this is a cash injection, i.e. Fed buys bonds directly)

Countless other global central banks have cut rates & injected cash into their economies as well

These are all financial crisis era policy tools the Fed has used previously, but at an unprecedented and swift scale. And Congress is looking at extending the Fed’s powers into new, previously unexplored domains as well. One such proposal is allowing it to buy corporate bonds directly.

What is all of this driving towards? What’s the goal? Shore up liquidity in markets.

What do we mean by that?

This is Water

There are these two young fish swimming along, and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says, "Morning, boys, how's the water?" And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes, "What the hell is water?" (source)

There are long periods of relative calm in markets and global economies where we take for granted that there is sufficient “liquidity” (read here as US dollars) around.

Then there are times, like now, where we realize that was a very thin veneer.

Liquidity is the water the financial system swims in. What do we mean by that?

For now, just imagine that key financial institutions, like major banks, which do a lot of the systemically necessary lending in the economy, are fish, swimming in this water. You and I are little plankton, happily assuming Robinhood is going to work tomorrow.

Now, things start happening. Everything starts getting relentlessly sold.

Stocks? Of course.

But treasury bonds, gold, silver, Bitcoin, all considered traditional safe haven assets? Those start selling as well.

As they have. Axios summed it up well on Thursday:

Gold dropped by 3% and U.S. and German government debt, viewed as the safest bonds on earth, were sold despite a 5% decline on the S&P 500 and a rout that saw WTI crude oil prices fall 14% and crash below $22 a barrel.

Further, over the weekend we’ve heard of two major banks needing to step in and support money market funds (short-term bond and cash funds), because so many customers have been liquidating for cash.

When markets seize up in this fashion, with investors of all shapes and sizes moving into defensive position, demand for cash rises, and the volume of trading in other key markets like equities and bonds starts thinning.

The biggest story here is in treasuries however.

Extending our water analogy, imagine the government’s treasury issuance like a sponge. The more treasuries issued, the bigger the sponge. This sponge soaks up water, which as we know in our analogy represents cash, specifically US dollars. The bigger the sponge, the more water it soaks up.

Big fish like Chase and Wells Fargo act as primary dealers; they buy treasuries directly from the government with the intention of then selling them to others. The more treasuries there are floating around in general, the more these primary dealers have to buy, and the less cash on hand they have. As early as 2019, primary dealers (banks) were already hoovering up ~40% of all the treasuries the government was issuing.

When banks have more treasuries and less cash on their balance sheets, they look for cash elsewhere. Repurchase transactions, which are a form of overnight lending, are one way of getting it, because they temporarily swap treasuries for cash. If lots of banks are looking to borrow in volume however (and often from each other) there may not be enough cash to go around.

Inject some market chaos in this landscape (investors stop buying treasuries) and you have a problem. It’s a big time dollar shortage. The sponge has soaked up all the water. The pond is dry. And the fish aren’t having a nice time. Enter the Fed’s big hose.

The Fed’s emergency policies can address all this in a few ways, some of which they’ve now implemented (and which we outlined earlier):

Make significant cash available for the aforementioned repurchase transactions

Buy treasuries the government is issuing so banks don’t have to

Open “swap lines” to loan cash overseas because other countries need dollars too (don’t ask - but see Lebanon as an early example of default)

All of this is happening at the scale of trillions of dollars of lending and billions of dollars of treasury purchases.

And yet, demand for dollars still isn’t waning. Against a basket of other currencies, the dollar still registered new highs this week (charts per Axios):

Nor is printing money to support new government deficits, while necessary in the short-term, a sustainable system long term. We’re not out of the woods yet.

In the same way that turning the US economy back on won’t be easy, unwinding these policies won’t be straightforward either. Even when coronavirus subsides, there’s a global shortage of dollars that existed before the virus and that has now been dramatically exacerbated.

What’s next and what matters?

Said plainly, need is non-linear. Those affected most viciously by everything we outlined will be the same ones who were hit hard by past economic crisis: the poor, the unemployed, the uneducated, the old, the sick. As you go out on the X axis of ‘relatively worse off to begin with’, the Y axis, ‘new harm done’, gets exponential.

None of the Fed’s policy actions reach these people first. Their policies shore up the big fish, not the plankton. We’re not bemoaning that fact. It is what it is.

A $2T fiscal stimulus package, brewing in congress, will help, but even that may, unbelievably, be a drop in the bucket. We don’t know.

What’d we’ll close with is this:

We can write this brief and sip kombucha and work remotely for as long as necessary. Others, not so much.

How do we efficiently distribute security from the part of the distribution we sit in to the already worse-off part, which is now more overwhelmed than ever?

The answer may begin with gift cards from local businesses. But it can’t end there.

We began this brief with a story about non-attachment for a reason.

In the coming months and weeks, we will need to be fundamentally unattached to our conceptions of how we invest our financial, human, and social capital.

Is the decade long paradigm of every U.S. stock with a pulse going inexorably higher over for good? Not sure, but we’d bet it won’t be that easy in coming months or years.

Is the way we work and the way we participate in local, national, and global economies going to change drastically? For sure. We can already hear the drumbeat of repatriating manufacturing from overseas, shoring up domestic-only supply chains, and calls for general national self-sufficiency more loudly and clearly than ever.

Similarly, and though we already bored you with it, global currency dynamics are in massive upheaval. That could land us anywhere.

Lastly, will we need to help our neighbors more than we’re accustomed to? Yes.

All this will require a lot of imagination. And non-attachment. One day at a time.

Much love,

N